The Origins of Bushidō

The

inciting event that gave birth to the bushi

was the Taika Land Reform of 645 AD and the

modifications to that reform that followed in the early

8th century. Prior to these land reforms all land

in Japan was the property of the imperial family.

Farmers lived on the imperial land and cultivated crops and raised

animals that were essentially rationed to the people by

administrators appointed by the Emperor. Those

doing the work received the same ration, regardless of

how productive or unproductive they were. As a

result, there was no incentive to produce high yields,

so there was insufficient food to feed the

population and starvation was rising in the early 7th

century.

The

inciting event that gave birth to the bushi

was the Taika Land Reform of 645 AD and the

modifications to that reform that followed in the early

8th century. Prior to these land reforms all land

in Japan was the property of the imperial family.

Farmers lived on the imperial land and cultivated crops and raised

animals that were essentially rationed to the people by

administrators appointed by the Emperor. Those

doing the work received the same ration, regardless of

how productive or unproductive they were. As a

result, there was no incentive to produce high yields,

so there was insufficient food to feed the

population and starvation was rising in the early 7th

century.

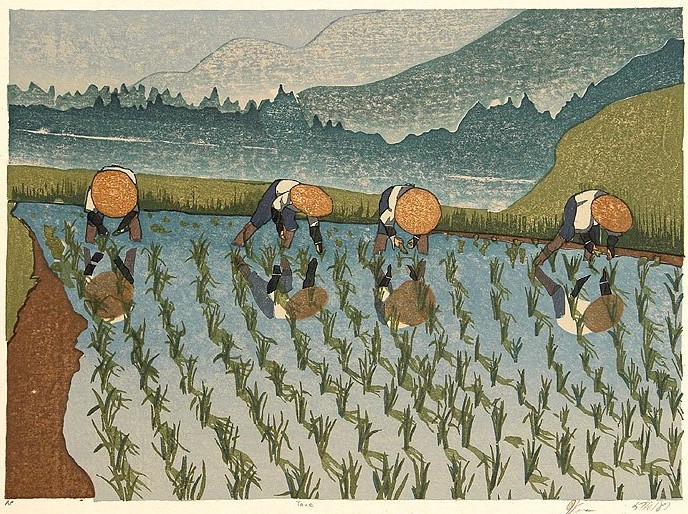

The Taika Land Reforms apportioned the large tracts of land formerly belonging to the imperial family into small plots for family farming. The families farming those plots were allowed to keep, and sell if they wished, any excess they produced over the taxes assessed on their land. At first, the lands were reapportioned every few years by census, but by the mid 8th century, the system was working so well and producing such abundance that families were allowed to permanently keep their lands, and to buy and sell those lands. Of course, human nature being what it is, greed resulted in increasing numbers of thefts and murders for some to acquire more land without paying or working for it. To protect themselves and their property, jinushi (landowners) began hiring guardians to protect their lives and property. Those guardians eventually came to be called bushi (武士) by the mid- to late-Heian Jidai (Heian Era). which lasted from 794 to 1185 AD.

Bushi (武士) does not mean "warrior." The kanji "bu" (武) is formed from two other kanji: dome (止), which means to stop, prevent, or quell, and hoko (矛), which is a type of spear and represents conflict, warfare, or rebellion. The kanji "shi" (士) in bushi means scholar, sage, wise man, or gentleman. There are several Japanese terms for warrior: senshi (戦士), heishi (兵士), gunjin (軍人), and heisotsu (兵卒) being among the most common. By definition, a warrior engages in warfare. A bushi first uses wisdom and diplomacy to prevent conflict and engages in combat only if forced to do so. A bushi defends the innocent and the victims of illicit aggression, while a warrior engages in combat whether as aggressor or defender. A bushi is thus better understood as a guardian of peace—a peacemaker or peacekeeper—rather than a warrior. In fact, a bushi might well be considered the antithesis of a warrior.

By the late Heian Jidai (794—1185 AD), the bushi had developed a lifetyle and unwritten code of ethics we now know as Bushidō, or the Way of the Bushi. As the power, reputation, and prestige of the bushi rose, the term "Bushidō," often stated as Bushi no Michi, came into popular use. At that time, the bushi were not samurai. Samurai (侍) were hereditary nobles and administrators appointed by the Emperor. They were primarily the record keepers, accountants, diplomats, and as the name "samurai" suggests, public servants during the Heian Jidai. It wasn't until the early Kamakura Jidai (1185—1333) and the establishment of the first Sei-i Tai-Shōgun (supreme military commander) as the de facto ruler of Japan that the bushi were granted samurai status. Even so, only vague references to Bushidō appear in Japanese literature or historical records prior to the Tokugawa Jidai (1603—1868), and those early references do not describe its principles in any useful detail; only that the bushi had a Way of Life that they, and the samurai class as a whole, devotedly followed.

The first known written use of the word Bushidō is found in the Kōyō Gunkan, a detailed account of the exploits, philosophy, and military campaigns of Takeda Shingen completed in 1616, but it contains only cursory mention of traits like duty, loyalty, courage, and honour. Two factors are likely to have played a role in defining Bushidō more specificially during the Tokugawa Era: the influence of Christianity and the pacification of Japan under the Tokugawa regime. With Japan at relative peace following some 500 years of nearly constant internal warfare between daimyō and roughly one-third of the samurai class becoming at least nominally Christian under the influence of Jesuit missionaries, the roles and purpose of the samurai and the bushi were changing significantly. No longer were physical battles and the need for courage and ferocity in combat a daily reality, so character traits like compassion, devotion to service, and honourable behaviour were of growing importance to the duties of civil administration, justice, and peacekeeping. A few similar referencees were made between the mid-17th century and the early 19th century, but the first published work to describe specific attributes and behaviours of Bushidō was actually written in English, in Monterey, California, in 1899 by a Japanese scholar and diplomat named Nitobe Inazō (1862—1933), who was a Christian. He described Bushidō in terms that are applicable to people of all religious and philosophical beliefs. It was this book that popularised the word Bushidō and the first seven of the eight traits cited here both in Japan and worldwide.